Par Quentin Lobbé, Doctorant en informatique et sociologie à Télécom ParisTech

À mesure que le train s’approche de Dunkerque, le relief se fait plus discret. S’affaisse. Répétitif, presque monotone. Au loin, la mer et – derrière – l’Angleterre pour seul horizon.

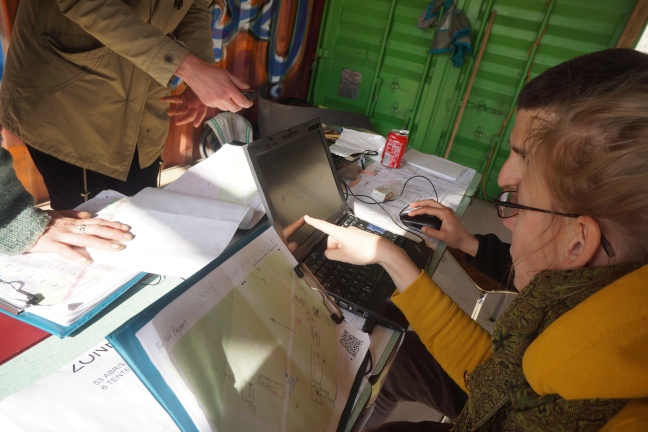

Je retrouve l’équipe de MapFugees : Katja, Jorieke et Johan. Ils sont là depuis une semaine déjà, éprouvés mais toujours aussi motivés. D’autres m’ont précédé, d’autres nous succéderons. L’équipe cherche à dresser une carte du camp de réfugiés de Grande-Synthe (proche de Dunkerque), nouvellement installé par Médecins sans frontières. La tâche n’est pas simple d’autant que nous partons de zéro : le camp était, il y a encore quelques semaines, une simple friche, les images satellites ne sont d’aucune utilité. Les résidents du camp participent au travail de cartographie, c’est une condition essentielle à la tenue du projet. Nous rassemblons rapidement le matériel, quelques ordinateurs, des clés 3G, des GPS, des chargeurs, des batteries et une montagne de Field Papers vierges ou déjà annotés. Le territoire occupé par le camp a été préalablement divisé en portions égales, imprimées sur papier en autant de Field Papers qui serviront de support à la récolte d’informations sur place. Chaque Field Paper est unique et porte la marque du binôme qui l’a édité : réfugié + bénévole + numéro du GPS + date, permettant de tracer et de suivre l’évolution du processus de cartographie de chaque zone.

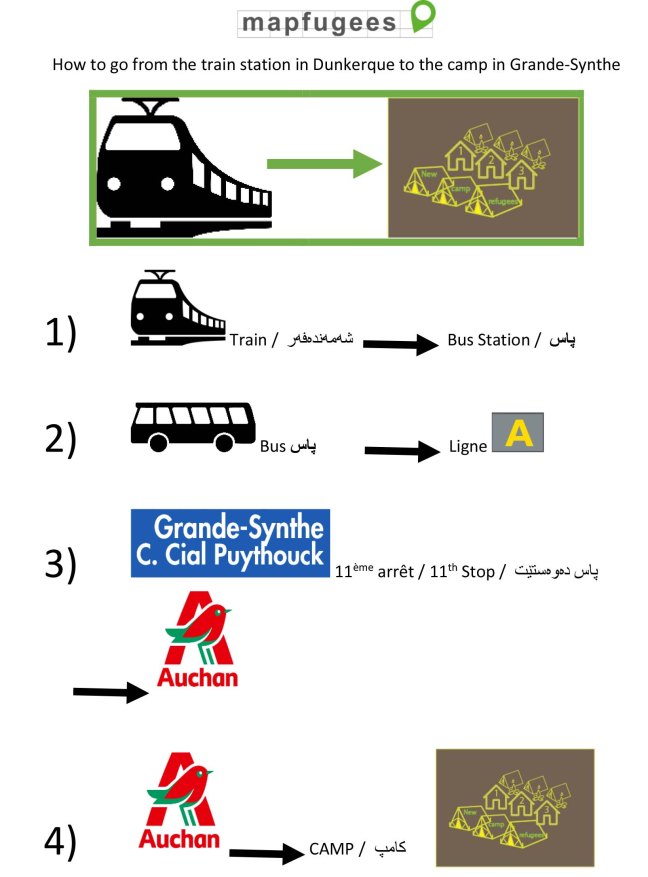

Nous nous mettons en route. Le bus quitte le centre de Dunkerque, longe le port, les quais et les ferrys en partance pour le Royaume-Uni. Nous arrivons aux abords d’une importante zone commerciale et industrielle prêt de Grande-Synthe. Il faut la traverser, longer routes et ronds-points et suivre un chemin balisé sur le terre-plein central d’une rocade avant d’atteindre le camp, dangereusement niché entre l’A16 et les lignes de trains reliant Dunkerque à Calais.

Les liens que nous tissons nous décrivent, façonnent nos appartenances et nos idées. Ils nous renforcent et nous aident à nous construire, parfois à tenir. Avec l’apparition de la figure du migrant connecté [1], il a définitivement été établi que les migrants étaient acteurs d’une culture de liens, renforcé par l’usage des TIC, ravivant sans cesse la flamme d’une pulsion de présence entre le pays quitté et le pays atteint. Cette proposition n’a jamais été aussi vraie qu’à la vue du camp de Grande-Synthe.

Le charging center est littéralement le cœur du camp, c’est le premier bâtiment que nous croisons une fois le seuil franchi. Bien avant les cuisines ou les points de ravitaillements en pétrole et vêtements. Des centaines de multiprises, de chargeurs et de câbles s’entremêlent, se croisent et se chevauchent sous ce vieux porche aménagé. Les réfugiés y patientent, discutent, échangent ou jouent au football en attendant que leurs batteries ne soient à nouveaux pleines.

Nous nous installons dos au conteneur qui sert de point d’accueil aux réfugiés. C’est un endroit stratégique et très passant où nous attirons le regard et la curiosité des résidents. Certains d’entre eux sont déjà là, habitués, ils nous attendent prêt à repartir cartographier. Après un rapide bilan, le processus de reconnaissance semble arriver à son terme, il ne reste que l’arrière du camp et les zones de vie (cuisines, échoppes, aires d’enfants…) à quadriller. Ces dernières sont particulièrement volatiles, de nouveau points d’intérêts apparaissent chaque jour, comme ce bike workshop qui n’était pas là la veille. Nous pourrions y revenir des dizaines de fois qu’il y aurait toujours quelque chose de nouveau à ajouter à la carte.

Comme je découvre le camp, A. – qui est arrivé à Grande-Synthe il y a une semaine à peine – se propose de m’accompagner et de m’enseigner la façon dont on cartographie les lieux. Il maîtrise déjà tous les outils. À ses côté je me sens élève brouillon, aux gestes mal assurés. Notre approche combine GPS et Field Papers qu’il annote. Nous remontons la Middle Road du camp, l’artère principale qui dessert toute la zone. Certains détails sont importants à relever comme cet alignement d’arbres qui délimitent un espace repas, des points de repères que l’on voit de loin, facile à identifier. Il s’agit plus de coucher sur papier la carte mentale qu’A. se fait du camp que de respecter des conventions de cartographes. Il faut avant tout respecter la construction que se font les résidents du camp. Quels en sont les frontières ? Les nœuds, les voies ou les repères visuels à la manière d’un Kevin Lynch [2].

A. m’indique les points d’intérêts manquants que nous pointons grâce au GPS et dont nous précisons les fonctions. Il s’agit de bien nommer les choses, il me reprend à de nombreuses reprises, ce Coffee Shop ci est en réalité un Coffee & Tea Shop. A. navigue entre les shelters (abris en bois de 8 m² installés par MSF), construisant son propre parcours, révélant sa façon de percevoir les lieux. C’est la structure même du camp qui se dessine alors sous nos yeux. Qui vit où ? Les familles à l’avant, les célibataires à l’arrière, les écoles au centre du camp… La carte finale proposera plusieurs layers. Plusieurs couches pour plusieurs usages. Les bénévoles, la logistique, les associations, les résidents. Tous doivent s’emparer de cet outil.

À mesure que nous nous enfonçons dans le camp, A. s’ouvre à moi. Cartographier le camp rompt avec la routine et l’ennui. Il raconte son histoire, sa vie d’avant, là-bas, au Kurdistan. Nous engageons la conversation avec d’autres réfugiés curieux de ce que nous faisons. A. en tire une certaine fierté, construire la carte noue des liens avec les résidents, avec les volontaires, avec chacun d’eux. Mais pour les réfugiés, les besoins en terme de carte vont déjà au-delà du camp, ils se tournent vers l’extérieur, hors la jungle de Grande-Synthe. Comment atteindre le centre de Dunkerque ? Comment se rendre à la poste ? Au Auchan ? Au lac pour pécher ? Où trouver du Wi-Fi ? La carte n’est vraisemblablement que le point de départ pour un nouveau travail de Way In qui s’ouvre à nous.

Nous rejoignons l’équipe, il reste à numériser notre travail. Télécharger les données, reporter les points, redessiner les contours de chaque bâtiment, catégoriser tel ou tel lieu puis, finalement, tout uploader sur OpenStreetMap (OSM). Il faut faire vite, l’autonomie de nos ordinateurs n’est pas illimitée, même pour nous la durée de vie d’une batterie est vitale. C’est le camp dans sa globalité qui semble construit autour de ce besoin de charger. Recharger. L’alimentation en électricité manque cruellement, l’arrivée d’une borne Wi-Fi est primordiale. Nous nous en sortons grâce à des clés 3G. Il est parfois possible de capter un réseaux ouvert, me dit A., mais cela ne dure pas longtemps. Se connecter devrait être un droit fondamental.

A. et moi devenons amis sur Facebook. Son smartphone regorge d’applications en tous genres, bien plus que le mien. Facebook, Whatsapp et Viber en tête. Il ne le quitte pas des yeux, tout le temps à le manipuler, vérifier sa messagerie. Il ne s’en séparerait pour rien au monde. En tout cas pas maintenant. Certaines applications lui ont déjà rendu de précieux services, Sygic, par exemple, lui permet d’avoir accès à un GPS sans connexion à internet.

En suivant le fil de son compte Facebook nous remontons à la source de son propre périple depuis la frontière irakienne, illustré de photos postées sur Instagram, comme autant de traces numériques laissées derrière lui. Il s’interrompt. De nouveaux messages. Sa famille restée au Kurdistan, ses amis sur le camp, ceux qui ont pu traverser. A. n’est jamais seul. Son téléphone porte la voix de tout ceux qui lui sont chers. Dans sa poche ils sont des centaines, peut être des milliers à l’accompagner.

De retour à Dunkerque, l’équipe passe une bonne partie de la nuit à faire du data cleaning, rectifier certains tracés de bâtis maladroits, dédoublonner les données… Katja doit modérer les contributeurs d’OpenStreetMap qui déjà derrière leurs propres écrans s’emparent de la carte, la modifient, l’améliorent. Comme elle le dit – « We don´t need a perfect map (yet). »

Au matin, la première version de la carte est prête, nous l’imprimons et l’apportons au camp. Il est 14h, Grande-Synthe s’éveille sous la pluie. La plupart des volontaires arrivent en même temps que nous. Il n’est de toute façons pas nécessaire de venir plus tôt, beaucoup de résidents ont passé la nuit dehors à essayer de rejoindre l’Angleterre. Ils sont rentrés tard et se lèvent à peine. Certains ne reviendront pas avant plusieurs jours, certains disparaissent. A. et les autres nous rejoignent au compte-gouttes, ensemble nous assemblons la carte que nous affichons sur le conteneur.

Voir la carte d’un seul tenant est un premier aboutissement et cela ouvre de nouvelles perspectives. Nous pouvons enfin prendre du recul sur le travail accompli. Avoir un regard critique. Les résidents s’approchent pointent du doigt des erreurs, des imprécisions. Quid de la traduction en Kurde ? L’un d’eux propose de s’en charger. Il manque les portes d’accès à la zone médicale, bien, A. et moi repartons GPS à la main. Faut-il séparer les douches des toilettes ? Certainement. Ils notent leurs noms à côté de leur shelter respectif. Ils s’approprient déjà la carte. Nous commençons à discuter d’un code couleur, par type de bâtiments. C’est par itération successive que la carte s’affine. D’autres questions fusent. Où afficher la carte dans le camp ? Quel format ? …

Nous terminons la journée en installant l’application OpenStreetMap sur les portables des réfugiés afin que la consultation de la carte soit rendue plus facile, l’édition également. La carte doit continuer à vivre et à évoluer après le départ de l’équipe. C’est impératif. Nous ouvrons un groupe Whatsapp afin d’échanger nos idées entre réfugiés et volontaires, se coordonner.

L’atmosphère change soudain, c’est perceptible. La vie dans le camp ralentit, les enfants rentrent, il est 18h. Ils sont déjà nombreux à se préparer pour la nuit à venir, dehors. À nouveau, chercher à traverser. À tout prix. Le charging center est bondé. Les téléphones toujours en prise. Trouver une route ou joindre un contact.

Sur le chemin du retour, longeant l’A16 et la rocade, nous croisons de nombreux réfugiés. Nous marchons quelques temps avec l’un d’entre eux. Partager sa trajectoire. Un sac et un violon pour bagage. Smartphone à la main. On nous avait vanté les mérites de sa musique dans le camp, mais n’avions pas eu la chance de l’entendre. Il est déterminé à partir. Ce soir. Il bifurque, traverse la voie rapide et se perd derrière le flots de voitures.

Les réfugiés sont les navigateurs modernes, se servant de leurs smartphones comme d’une boussole. À l’ombre de la ville de Jean Bart, l’espoir, parfois, peut tenir à une connexion 3G.

[1] Dana Diminescu, Le migrant connecté, pour un manifeste épistémologique, 2005

[2] Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City, 1960

welcoming, but spoke little english. I had a very slow conversation with him, using google translate on his phone, and all relayed to his wife. Again they had spent about a month travelling to get to Dunkirk. He had worked as a sports teacher in Iraq. He mimed to explain how they had left because of the constant bombing and gun fire every night. I can imagine there wasn’t much call for sports teachers or any kind of life for his two young kids in that environment. I asked him how much stuff they had travelled with. His wife started crying when he relayed that question. I guess they were once a reasonably well off middle-class family, but they left it all behind and ended up here with nothing but a shed and some blankets. I worried that they might think I was able to help them get into the UK somehow, so I explained that I was just here to try to make life in the camp a little better, by creating a map.

welcoming, but spoke little english. I had a very slow conversation with him, using google translate on his phone, and all relayed to his wife. Again they had spent about a month travelling to get to Dunkirk. He had worked as a sports teacher in Iraq. He mimed to explain how they had left because of the constant bombing and gun fire every night. I can imagine there wasn’t much call for sports teachers or any kind of life for his two young kids in that environment. I asked him how much stuff they had travelled with. His wife started crying when he relayed that question. I guess they were once a reasonably well off middle-class family, but they left it all behind and ended up here with nothing but a shed and some blankets. I worried that they might think I was able to help them get into the UK somehow, so I explained that I was just here to try to make life in the camp a little better, by creating a map.